Abstract

Various strains can be found in emphysematous prostatic abscesses (EPAs), but the most frequent causative organism is Klebsiella pneumoniae. Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae can disseminate to distant sites by forming a muco-polysaccharide network outside the capsule. Here, we present the first case of K. pneumoniae in an EPA accompanied by a spinal cord infarction. A 65-year-old man was referred to our hospital due to sudden-onset paraplegia after a 5-day history of fever, myalgia, and voiding difficulty. Abdominal computed tomography revealed a collection of air pockets in the prostate, and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed high signal intensity in the thoracic spinal cord. The patient was initially treated with antibiotics and surgical drainage. On the third hospital day, therapeutic heparin was added after discussion with a neurologist. The patient had no inflammatory symptoms, experienced some improvement in paraplegia, and was discharged on the 14th hospital day. This study adhered to the case report guidelines.

-

Keywords: Prostatitis, Abscess, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Embolism, Case report

HIGHLIGHTS

This case report presents the first documented instance of a Klebsiella pneumoniae-induced emphysematous prostatic abscess (EPA) accompanied by spinal cord infarction. The 65-year-old diabetic patient exhibited sudden-onset paraplegia, fever, and urinary symptoms. Diagnostic imaging revealed air pockets in the prostate and high signal intensity in the thoracic spinal cord. Treatment included antibiotics, surgical drainage, and anticoagulation. The patient showed partial improvement in neurological symptoms within 2 weeks.

An emphysematous prostatic abscess (EPA) is a rare condition in which gas-forming organisms form gas pockets inside and around the prostate. A variety of strains can form gas in the urinary tract mucosa; however, the most common causative organism of EPA is

Klebsiella pneumoniae [

1]. Since clinical

K. pneumoniae strains usually form hypermucoviscous colonies, they can form septic emboli or cause metastatic infections in other organs [

2,

3]. Although a case of emphysematous prostatitis complicating septic pulmonary emboli has been previously reported [

4], to the best of our knowledge, spinal cord infarction caused by septic emboli in an EPA has not been reported. Here, we present the first case of

K. pneumoniae-induced EPA accompanied by a spinal cord infarction identified using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (DWI).

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old male with a history of insulin-dependent diabetes presented with sudden-onset paraplegia, lower limb dysesthesia, and urinary retention. He had fever, myalgia, and dysuria for the past 5 days, but did not receive any specific treatment. According to the physical examination, his peripheral temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate were 38°C, 110/80 mmHg, and 115 beats per minute, respectively. The lower abdomen was distended, and the local heating sensation and tenderness around the prostate were evaluated during digital rectal examination. Deep tendon reflexes and plantar responses of both lower limbs were reduced. Laboratory investigations revealed leukocytosis (white cell count, 19,040/μL), anemia (hemoglobin, 11.9 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 77,000/mm

3), elevated C-reactive protein levels (269 mg/L), hyperglycemia (serum glucose, 372 mg/dL), and hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin, 2.7 g/ dL). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.48, PaCO

2 of 33 mmHg, PaO

2 of 88 mmHg, blood eosinophil basophil of 1.1, and HCO

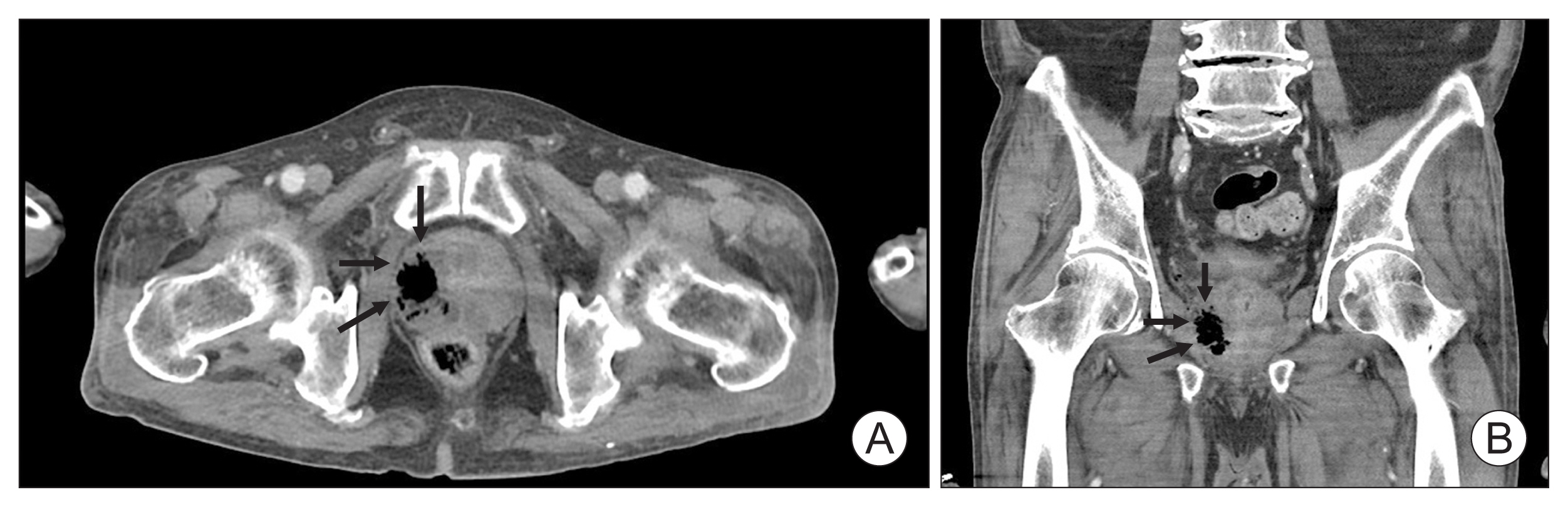

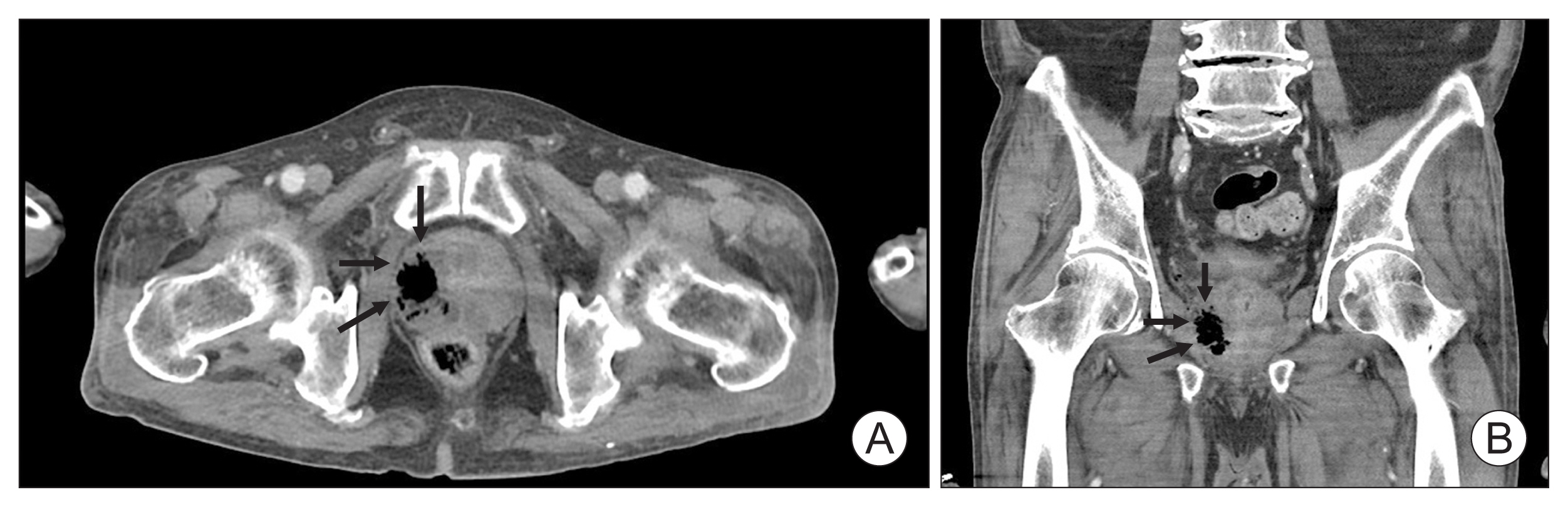

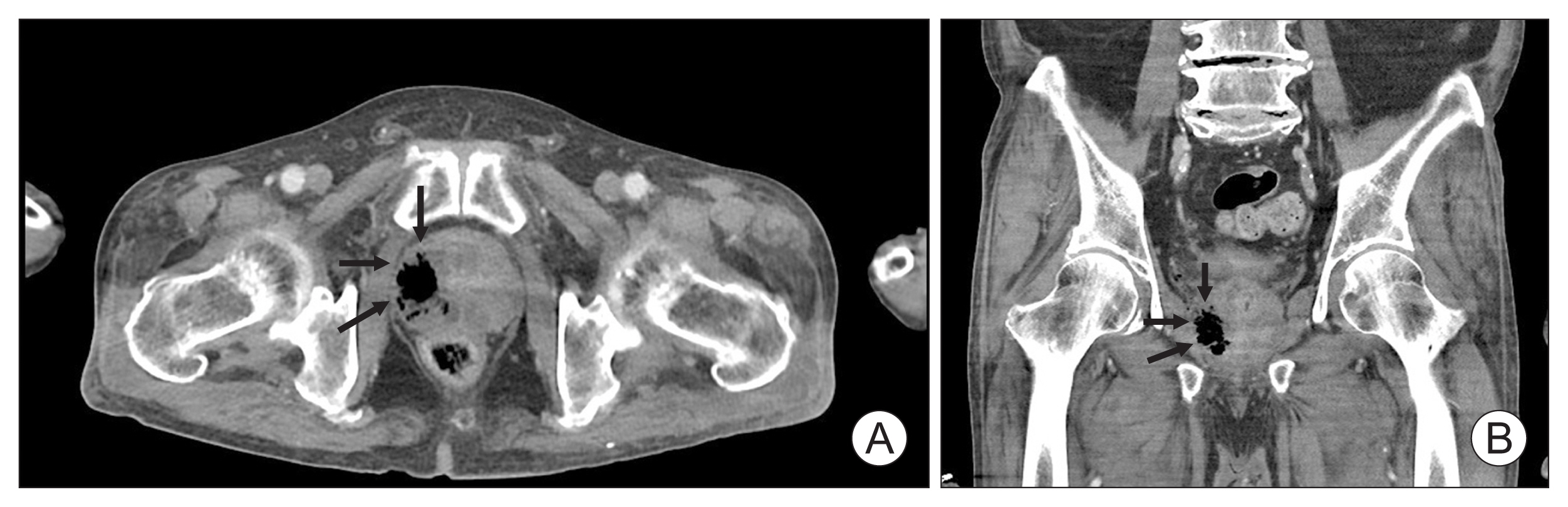

3− of 24 mmol/L. Spot urine examination revealed pyuria. An abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a collection of air pockets in the prostate (

Fig. 1A and B), and both kidneys were normal, with no dilatation of the excretory cavities. High signal intensity in the thoracic spinal cord was observed on isotropic diffusion-weighted MRI conducted for neurological evaluation (

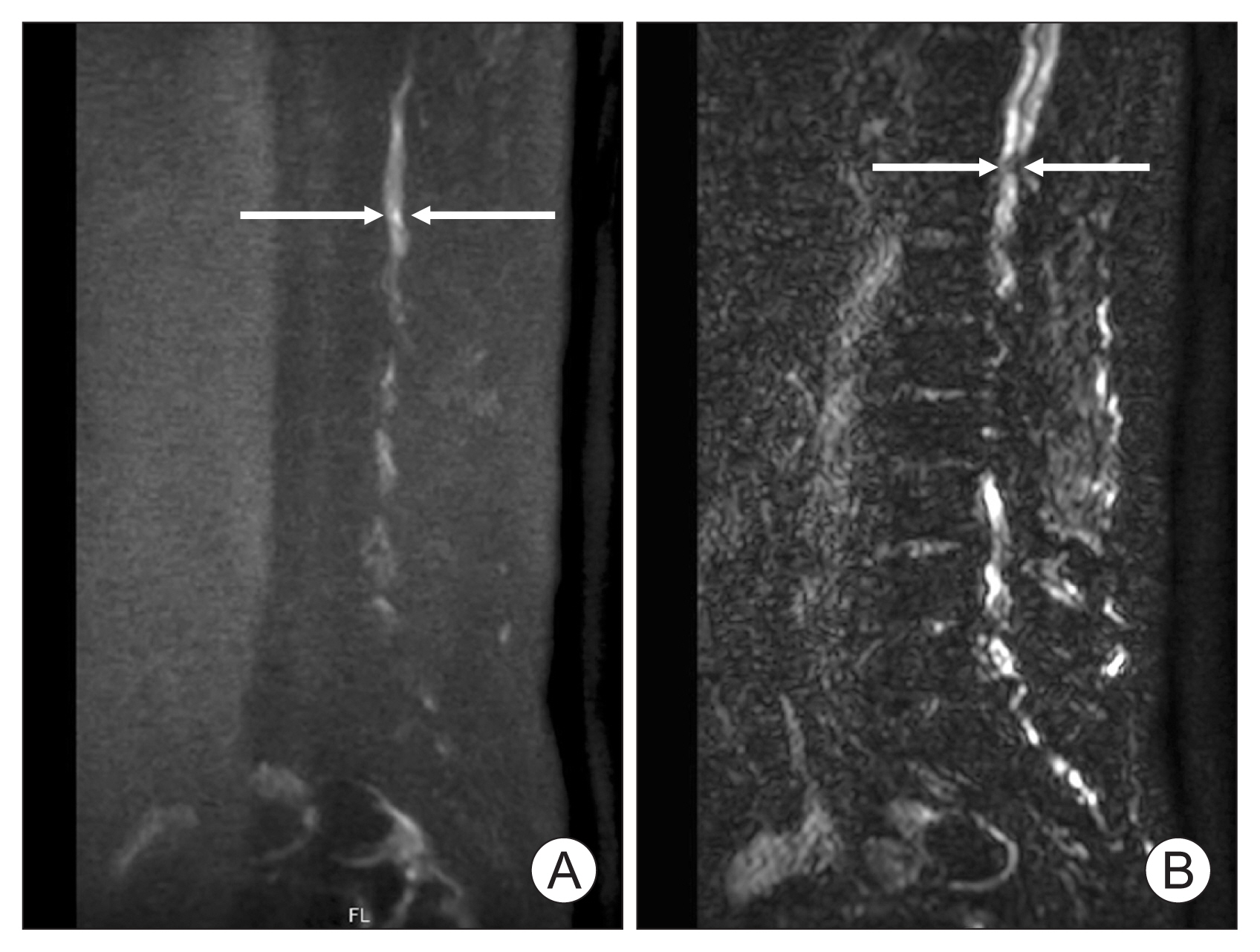

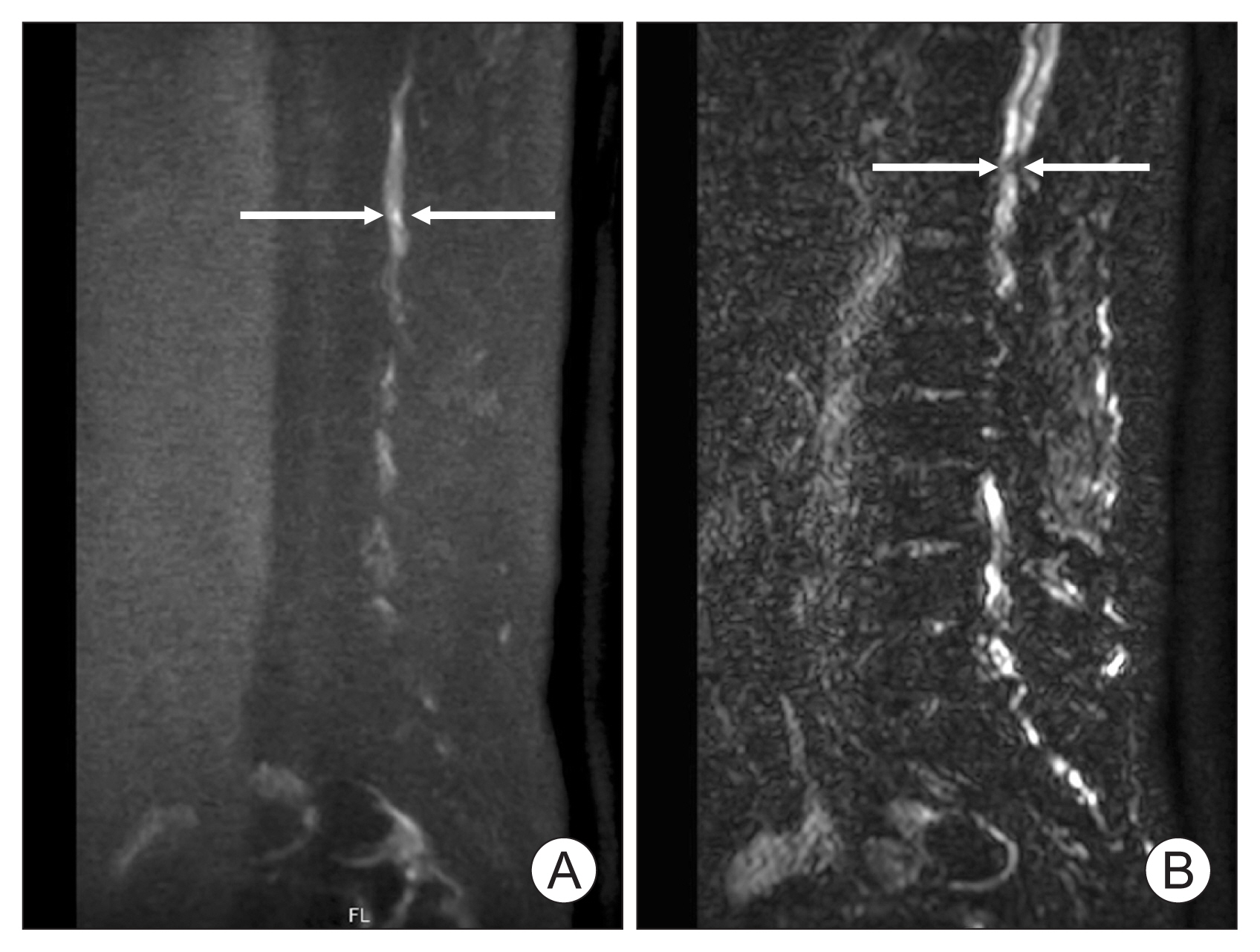

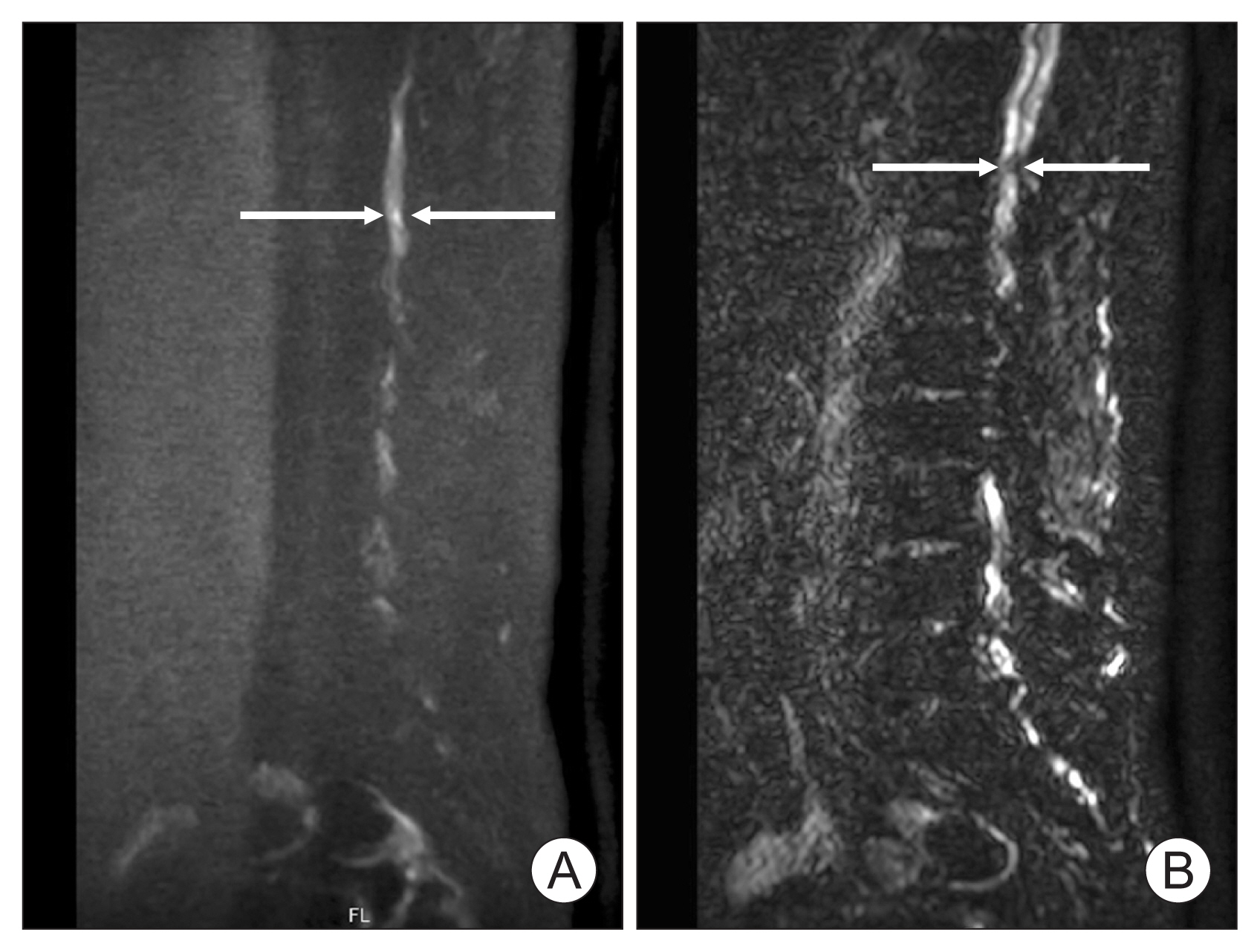

Fig. 2A). The apparent diffusion coefficient map showed a decrease in water self-diffusion in this area (

Fig. 2B). Based on clinical and DWI findings, the patient was diagnosed with a spinal cord infarct.

Empirical intravenous ceftriaxone was initially administered and then changed to tazoperan in accordance with the culture reports of the isolated K. pneumoniae. Suprapubic catheterization and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) were performed to drain the abscess. TURP was performed under general anesthesia, and the surgery time was 42 minutes. A procedure starts with the lateral parts of the gland (between 7 and 11 o’clock), followed by ventral lobe, the midlobe, and finishing with the apex. An additional resection at the opposite site was performed to improve urinary obstruction. Histopathological examination of the resected tissue revealed numerous inflammatory cells and necrotic tissues.

On day 3, the patient was apyretic, laboratory investigations demonstrated regression of the biological inflammatory syndrome, with white blood cells at 12,560/μL and C-reactive protein level at 84.6 mg/L.

The dysesthesia of his lower limbs slightly improved, but paraplegia persisted; therefore, therapeutic heparin infusion was initiated after an extensive risk vs benefit discussion with a neurologist.

On day 10, the blood and repeat urine cultures tested negative. Follow-up transrectal ultrasonography showed resolution of the abnormal air collection in the prostate.

On day 14, the dysesthesia in his lower limbs improved, and paraplegia also recovered to a Medical Research Council motor score of 3 out of 5. Furthermore, after suprapubic catheter clamping, he was able to urinate independently and was discharged with the suprapubic catheter removed. He was treated with anticoagulation, and 9 months following presentation he maintained self-urination but remained wheelchair bounded.

This report was approved by the Gyeongsang National University Hospital Institutional Review Board (GNU 2024-10-019). The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this case.

DISCUSSION

EPA is a rare but potentially severe disorder first described by Mariani et al. [

5] in 1983, and several cases have subsequently been reported. Most patients are aged in their 50s or 60s [

6] and have risk factors for diabetes mellitus, bladder outlet obstruction, bladder catheterization, and prior genitourinary tract instrumentation. The most common causative organism is

K. pneumoniae [

1], and in our case, it was also verified in urine and blood cultures.

K. pneumoniae is a pathogen with various clinical manifestations, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and other suppurative infections [

1,

2,

7,

8]. In particular, hypervirulent

K. pneumoniae demonstrates a mucoviscous phenotype by forming a mucopolysaccharide network outside the capsule [

9] and also causes metastatic infections [

10]. Primary

K. pneumoniae liver abscesses or EPA can reportedly cause metastatic infections, such as pneumonia, endophthalmitis, splenic abscess, and pyogenic arthritis [

11–

13]. However, to the best of our knowledge, spinal cord infarction due to septic emboli in EPA has not been reported.

Escherichia coli,

Proteus mirabilis, Citrobacter species, and yeasts can also form H

2 and CO

2 gas in the urinary tract mucosa through the fermentation of substrates such as glucose and albumin in necrotic tissues [

14]. EPA can be diagnosed radiologically by the presence of gas in the prostate. A gas shadow in the prostate can be confirmed through a plain film of the kidney, ureter, and bladder, it is often difficult to distinguish it from the surrounding bowel gas shadow. CT is considered the best diagnostic modality for EPA because it can be used to check the distribution and amount of gas in the prostate. It may also provide prognostic information in conjunction with clinical signs and symptoms.

Emphysematous prostatitis can be treated with a combination of broad-spectrum antibiotics and abscess drainage. Abscess drainage can be performed using transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) or CT-guided needle aspiration, open perineal incision, or TURP. Since TRUS- or CT-guided needle aspiration can be conveniently performed under local anesthesia, it can induce more effective symptom improvement than the use of antibiotics alone at the acute infectious stage. However, if access with a needle is difficult or if there are many abscess debridements, it may be difficult to remove sufficient abscesses using needle aspiration alone, which may require repeated procedures. TURP requires spinal anesthesia, but because it unroofs the abscess pocket, it can drain a large number of abscesses in a short time and simultaneously improve bladder outlet obstruction.

Our case was somewhat atypical because it was accompanied by spinal cord infarction. Spinal cord infarcts can be diagnosed by identifying the characteristic neurological symptoms and ischemic lesions on MRI. Our patient had a sudden onset of paraplegia, dysesthesia of his lower limbs, urinary retention, and high signal intensity on DWI, but T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI showed normal findings. However, this discrepancy is often observed in acute spinal cord infarct at an early stage.

In 1940, Batson identified the anastomosis of the prostatic venous plexus and the vertebral and cranial venous systems (Batson plexus). Batson plexus is a system of valveless venous networks that surrounds the spinal cord and vertebral column, and it may also be a route for the direct propagation of prostate cancer, infection, or emboli to the spinal canal or brain. In our patient, Batson plexus could explain the mechanism by which the septic emboli of the prostate abscess migrated to the spinal canal. The treatment of spinal cord infarcts lacks standard guidelines and varies according to the etiology and clinical symptoms. Our patient received both antibiotic and anticoagulant treatments and exhibited partial improvement in neurological symptoms within 2 weeks.

In summary, EPAs are rare, and their symptoms are similar to those of acute prostatitis, making their diagnosis difficult. CT and TRUS may help in establishing this complex diagnosis. The management of EPAs includes appropriate surgical drainage and antibiotics. Microorganisms from a prostatic abscess can disseminate into the spinal cord, brain, and lungs through Batson plexus; therefore, primary physicians should be mindful of the possibility of meningitis or spinal cord infarction when treating patients presenting with prostate abscess accompanied by neurological symptoms.

NOTES

-

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

-

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: SUJ, SCK, JSH, JSH; Data curation: SUJ, CP, MSC, CSK, DHK, JHC, SMC; Writing - original draft: SUJ, JSH; Writing - review & editing: SUJ, CP, MSC, CSK, DHK, JHC, SMC, SCK, JSHwa, JSHyun.

Fig. 1Pelvic computed tomography (CT) reveals an enlarged prostate with a low attenuating, well-defined lesion consistent with gas and abscess formation (arrows). Axial (A) and coronal (B) pelvic CT images.

Fig. 2Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine. (A) Sagittal diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed a high intensity signal at thoracic spinal cord (arrows). (B) Apparent diffusion coefficient map showed a decrease in water self-diffusion in that area (arrows).

REFERENCES

- 1. Konagaya K, Yamamoto H, Suda T, Tsuda Y, Isogai J, Murayama H, et al. Ruptured emphysematous prostatic abscess caused by K1-ST23 hypervirulent klebsiella pneumoniae presenting as brain abscesses: a case report and literature review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;8:768042.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:881-7.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Yi JR, Yoon Y, Jung YN, Lee HS, Jo GH, Jeong I. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess complicated with septic pulmonary embolism. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2013;17:239-43.Article

- 4. Liu JW, Lin TC, Chang YT, Tsai CA, Hu SY. Prostatic abscess of Klebsiella pneumonia complicating septic pulmonary emboli and meningitis: a case report and brief review. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2017;10:102-5.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Mariani AJ, Jacobs LD, Clapp PR, Hariharan A, Stams UK, Hodges CV. Emphysematous prostatic abscess: diagnosis and treatment. J Urol 1983;129:385-6.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Thorner DA, Sfakianos JP, Cabrera F, Lang EK, Colon I. Emphysematous prostatitis in a diabetic patient. J Urol 2010;183:2025.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Fang CT, Chen YC, Chang SC, Sau WY, Luh KT. Klebsiella pneumoniae meningitis: timing of antimicrobial therapy and prognosis. QJM 2000;93:45-53.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Kuo PH, Huang KH, Lee CW, Lee WJ, Chen SJ, Liu KL. Emphysematous prostatitis caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Formos Med Assoc 2007;106:74-7.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Alcántar-Curiel MD, Girón JA. Klebsiella pneumoniae and the pyogenic liver abscess: implications and association of the presence of rpmA genes and expression of hypermucoviscosity. Virulence 2015;6:407-9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Li W, Sun G, Yu Y, Li N, Chen M, Jin R, et al. Increasing occurrence of antimicrobial-resistant hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in China. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:225-32.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Liu YC, Yen MY, Wang RS. Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess: their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1557-9.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Tsay RW, Siu L, Fung CP, Chang FY. Characteristics of bacteremia between community-acquired and nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: risk factor for mortality and the impact of capsular serotypes as a herald for community-acquired infection. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1021-7.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Abdul-Hamid A, Bailey SJ. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess and endophthalmitis. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013008690.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Hawtrey C, Williams J, Schmidt J. Cystitis emphysematosa. Urology 1974;3:612-4.ArticlePubMed

, Min Sung Choi1

, Min Sung Choi1 , Chang Seok Kang1

, Chang Seok Kang1 , Dae Hyun Kim1

, Dae Hyun Kim1 , Jae Hwi Choi1

, Jae Hwi Choi1 , See Min Choi1

, See Min Choi1 , Sung Chul Kam2

, Sung Chul Kam2 , Jeong Seok Hwa1

, Jeong Seok Hwa1 , Jae Seog Hyun1

, Jae Seog Hyun1

KAUTII

KAUTII

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite