Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors of Fournier Gangrene: A 15-Years Multicenter Retrospective Study in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Fournier gangrene (FG) is a rare but life-threatening necrotizing infection requiring prompt recognition and intervention. This multicenter study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes including mortality, and risk factors associated with death among patients with FG over the past 15 years in Korea.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 84 patients diagnosed with FG between 2008 and 2022 across 7 hospitals. Demographics, comorbidities, laboratory findings, and clinical outcomes were analyzed. Mortality-related risk factors were assessed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

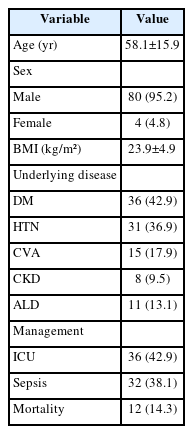

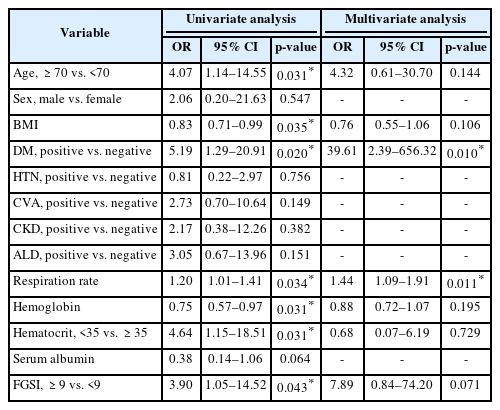

The mean age was 58.1±15.9 years, and 95.2% of patients were male. Diabetes mellitus (42.9%) and hypertension (36.9%) were the most prevalent comorbidities. Sepsis developed in 38.1% of patients, and the overall mortality rate was 14.3%. In univariate analysis, age ≥70 years, low body mass index, diabetes mellitus, low hemoglobin, low hematocrit, high respiratory rate, and Fournier gangrene severity index (FGSI) ≥9 were significantly associated with mortality. After data correction and multivariate adjustment, diabetes mellitus (odds ratio [OR], 39.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.39–656.32; p=0.010) and respiratory rate (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.09–1.91; p=0.011) were identified as independent predictors of mortality. FGSI≥9 demonstrated borderline association with mortality (p=0.08), indicating its potential clinical relevance.

Conclusions

In this multicenter Korean cohort, the mortality rate of FG remained substantial at 14.3%. Diabetes mellitus and elevated respiratory rate were independent predictors of mortality, while FGSI≥9 demonstrated a borderline yet clinically meaningful association, suggesting its role as a useful severity indicator in early risk stratification.

HIGHLIGHTS

This multicenter retrospective study analyzed 84 Korean patients with Fournier gangrene over 15 years. Diabetes mellitus and elevated respiratory rate were identified as independent predictors of in-hospital mortality, while Fournier gangrene severity index ≥ 9 showed borderline significance. Despite advances in care, mortality remained substantial (14.3%), underscoring the need for early risk stratification and multidisciplinary management.

INTRODUCTION

Fournier gangrene (FG) is a rapidly progressive necrotizing soft-tissue infection of the perineal, genital, or perianal regions that requires immediate recognition and urgent surgical management because of its high lethality [1]. FG is now recognized across a broad clinical population and typically arises from identifiable urogenital or anorectal sources of infection. Its clinical course is driven by polymicrobial synergistic tissue destruction, frequently resulting in sepsis and multiorgan dysfunction [2,3].

Despite advances in critical care, infection control, and surgical reconstruction, mortality remains substantial. Contemporary studies report mortality rates ranging from approximately 7% in population-based cohorts to over 20%–30% in tertiary referral center case series, reflecting disease heterogeneity and severity among hospitalized patients [1-4]. Moreover, a systematic review of 6,152 patients demonstrated that mortality associated with FG has not significantly improved over the past 25 years [5].

Predisposing comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, renal impairment, chronic liver disease, and immunocompromised states are frequently implicated in disease severity and adverse outcomes [6]. In addition, physiologic derangement at presentation, including tachycardia, hypotension, electrolyte imbalance, and elevated inflammatory markers, correlates with higher mortality risk [3,7-10]. Several prognostic scoring systems, such as the Fournier gangrene severity index (FGSI), Uludag FGSI, and Simplified FGSI, have been proposed to stratify risk, yet their generalizability remains limited due to inconsistent performance across different patient populations [11-17].

In Asia, particularly Korea, reports of FG have largely been confined to small single-center experiences, limiting understanding of disease epidemiology, treatment strategies, and predictors of mortality in this region [7-10]. A growing burden of metabolic disease and aging demographics suggests that FG outcomes in the Korean population warrant focused investigation.

Therefore, the present multicenter study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes including mortality, and risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality among patients with FG over the past 15 years in Korea. Findings from this study may help improve early risk stratification and guide timely intervention strategies tailored to Asian patient populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study Design

This study was designed as a retrospective multicenter cohort study and is reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Medical Center (IRB No. SEOUL 2025-07-005). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

2. Study Population

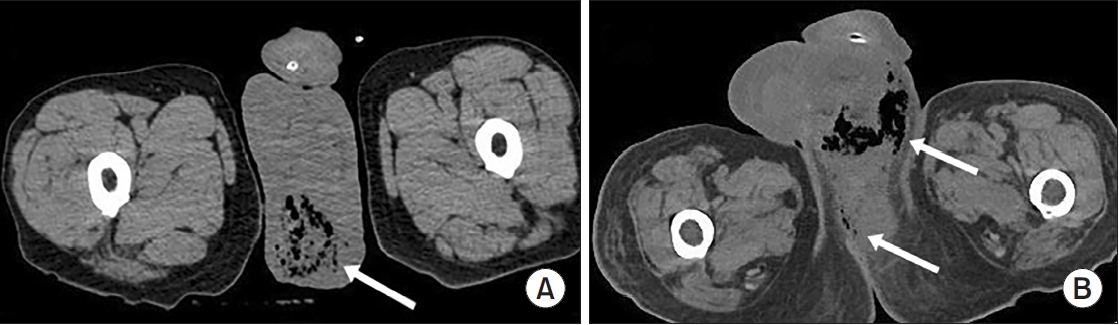

We reviewed the medical records of 84 consecutive adult patients diagnosed with FG between January 2008 and December 2022 across 7 hospitals in Korea. Patients were included if FG was diagnosed based on clinical features (perineal and/or genital necrotizing infection) together with supporting laboratory findings and radiologic confirmation, primarily computed tomography (CT) consistent with necrotizing soft-tissue infection. Patients with incomplete records regarding clinical outcome or those who presented with nonnecrotizing perineal infections were excluded.

3. Data Collection and Variables

Demographic characteristics (age, sex), comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and alcoholic liver disease), laboratory parameters at presentation, and clinical outcomes including sepsis and in-hospital mortality were collected.

Vital signs (respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature) and laboratory parameters were recorded at the time of emergency room arrival, representing the initial presentation values prior to surgical intervention. Sepsis was defined according to the Sepsis-3 consensus criteria using clinical and laboratory evidence of organ dysfunction [18]. The FGSI was calculated for each patient according to the original description by Laor et al. [17]. FGSI consists of 9 variables (body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, serum sodium, potassium, creatinine, bicarbonate, hematocrit, and white blood cell count) each scored from 0 to 4 based on deviation from the normal range. The sum of these component scores yields a total FGSI ranging from 0 to 36, with higher values indicating greater physiologic derangement and increased mortality risk. In this study, FGSI values were calculated using the vital signs and laboratory results obtained at initial presentation.

4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included sepsis occurrence and intensive care unit (ICU) admission. To assess temporal changes in mortality, the study period was stratified into 2 decades (2008–2016 and 2017–2022). In addition, risk factors associated with mortality were evaluated. When available, abscess culture results were recorded and categorized by organism.

5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means±standard deviation and compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (%) and compared using chi-square or Fisher exact tests as appropriate. Risk factors associated with mortality were identified using univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis, presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the analysis of risk factors associated with mortality, we assessed potential multicollinearity between respiratory rate and FGSI, as respiratory rate is a direct component of the FGSI. Variance inflation factor analysis demonstrated acceptable values (<2.5), suggesting no significant multicollinearity. Variables with p<0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into multivariable models. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 26.0 (IBM Corp., USA).

RESULTS

1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 84 patients were included in this study. The mean age was 58.1±15.9 years, and 95.2% were male. The most common comorbidity was diabetes mellitus (42.9%), followed by hypertension (36.9%). Sepsis occurred in 38.1%, ICU care was required in 42.9%. Among patients who required ICU care, the mean ICU stay was 8.0 days. The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 14.3% (Table 1). The most frequent organisms from abscess cultures were E. coli (29.8%) and K. pneumoniae (19.0%), with Staphylococcus spp. and other organisms comprising 10.7% and 33.3%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Representative CT images from 2 illustrative cases are shown in Fig. 1.

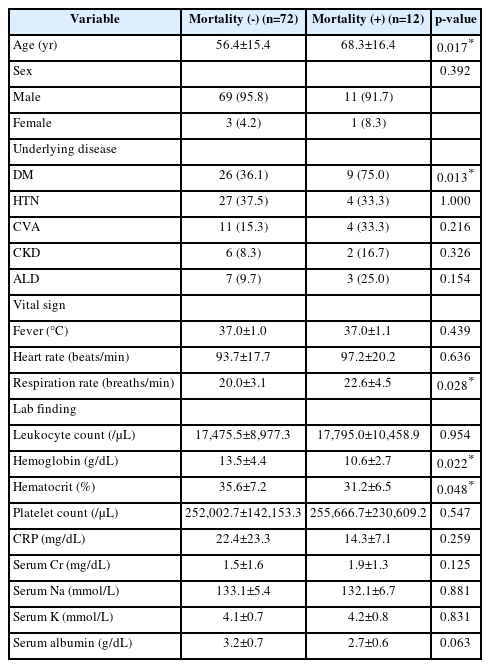

2. Comparison Between Survivors and Nonsurvivors

Compared to survivors, patients in the mortality group were significantly older (68.3±16.4 years vs. 56.4±15.4 years, p=0.017) and had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (75.0% vs. 36.1%, p=0.013). Nonsurvivors also showed significantly higher respiratory rate (22.6±4.5 breaths/min vs. 20.0±3.1 breaths/min, p=0.028) and lower hemoglobin (10.6±2.7 g/dL vs. 13.5±4.4 g/dL, p=0.022) and hematocrit (31.2%±6.5% vs. 35.6%±7.2%, p=0.048) levels at presentation (Table 2). There were no significant differences in heart rate, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, creatinine, sodium, or potassium levels between the 2 groups.

3. Risk Factors Associated With Mortality

Univariate analysis identified age ≥70 years, low body mass index, diabetes mellitus, low hemoglobin, low hematocrit (<35%), high respiratory rate, and FGSI ≥9 as significant predictors of mortality. In multivariate analysis, diabetes mellitus remained a robust independent risk factor (OR, 39.61; 95% CI, 2.39–656.32; p=0.010). Respiratory rate also remained independently associated with mortality (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.09–1.91; p=0.011). FGSI ≥9 did not reach conventional significance (p=0.071), but demonstrated a borderline association, suggesting clinical relevance in severity assessment (Table 3).

4. Temporal Trend in Mortality

To evaluate temporal trends in outcomes, patients were stratified by diagnosis year using 2016 as the cut-off (2008–2016 vs. 2017–2022). The mortality rates did not differ significantly between periods (13.8% vs. 14.8%, p=1.000). This indicates no evidence of improved survival in more recent years.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter Korean cohort of patients with FG, we observed a persistently high in-hospital mortality rate of 14.3%, which remained unchanged between the earlier (2008–2016) and more recent (2017–2022) periods. These findings mirror those from international studies demonstrating that despite substantial advances in critical care and infection management, FG-associated lethality has not significantly improved over the past 2 decades [5].

Diabetes mellitus emerged as a strong independent predictor of death in this study, consistent with previous investigations [1,2,6-8]. Hyperglycemia and immune dysfunction are believed to contribute to impaired neutrophil function, delayed wound healing, and enhanced susceptibility to polymicrobial necrotizing infection, ultimately worsening systemic deterioration [1,2]. In our cohort, nearly half of the patients had diabetes mellitus, reflecting the growing metabolic disease burden in Korea and underscoring the need for aggressive metabolic control and early infection surveillance in this population.

In our study, elevated respiratory rate was independently associated with mortality. This finding aligns with the pathophysiology of sepsis, in which tachypnea reflects compensatory hyperventilation for metabolic acidosis, hypoxemia, and evolving organ dysfunction [19]. According to the Sepsis-3 framework, the qSOFA (quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment) score assigns one point for respiratory rate ≥ 22/min, and higher scores are strongly associated with mortality in infected patients [18,20]. Likewise, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome definition includes respiratory rate > 20/min (or PaCO₂ < 32 mmHg) as a criterion of systemic inflammatory response [21]. These established sepsis-related criteria support our observation that increased respiratory rate represents early systemic deterioration and may serve as a valuable bedside predictor of mortality in Fournier gangrene.

Although FGSI≥9 was not statistically significant after adjustment, it demonstrated a borderline association with mortality. FGSI remains one of the most widely recognized severity scoring tools, and its clinical value as a triage adjunct should not be underestimated [9,11-13]. Although FGSI≥9 has been validated as a strong prognostic tool in prior studies, its borderline association with mortality in our cohort may reflect several interacting influences. The small number of deaths limits the analytic power, and variability in the timing and accuracy of baseline physiologic measurements may contribute to the score.

Interestingly, our temporal analysis did not show meaningful improvement in mortality among Korean patients. Prior meta-analyses have likewise reported stagnant mortality trends globally, despite better diagnostic imaging and intensive care availability [4,5]. Similarly, a recent Korean single-center study involving 35 patients also reported comparable mortality rates [17]. Several factors may contribute to our results, including older patient age, increasing comorbidity burden such as diabetes, and potential referral bias concentrating more severe cases in tertiary centers. Further national strategies supporting early recognition and standardized multidisciplinary pathways may be essential for improving outcomes.

This study expands current knowledge by presenting contemporary data from multiple Korean hospitals, adding region-specific epidemiologic insights to the predominantly Western literature. Nevertheless, several limitations warrant consideration. The retrospective design may introduce selection bias and underestimation of disease severity. Variations in management strategy across institutions were not fully adjusted for. Finally, the relatively small number of deaths constrained statistical power in prognostic modeling.

Despite these limitations, our study identifies readily measurable predictors including diabetes mellitus and respiratory rate that can guide timely intervention, especially in resource-limited or frontline settings. Moreover, the absence of improvement in survival outcomes highlights that FG remains a critical emergency in Korea, necessitating continued vigilance, early surgical control, and aggressive resuscitation.

CONCLUSIONS

In this multicenter Korean cohort, the mortality rate of FG was 14.3%, remaining substantial without significant improvement in recent years. Diabetes mellitus and elevated respiratory rate were the strongest independent predictors of in-hospital mortality, while FGSI≥9 showed a borderline yet clinically relevant association with disease severity. Early recognition of high-risk patients and timely multidisciplinary management are essential to improve outcomes in this life-threatening condition.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1 is available at https://doi.org/10.14777/uti.2550036018.

Distribution of organisms isolated from abscess cultures in patients with Fournier gangrene.

Notes

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Research Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul Medical Center (IRB No. SEOUL 2025-07-005). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Conflict of Interest

SKC and JSH are authors of this article as well as editorial board members of Urogenital Tract Infection. However, they had no involvement in the editorial evaluation or the decision to publish this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: CSK, HLL, THK; Data curation: CSK, HLL, JWL, JSH, YK, SB, THK; Formal analysis: CSK; Methodology: CSK, HLL, THK; Project administration: CSK; Visualization: CSK; Writing - original draft: CSK; Writing - review & editing: CSK.