Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Older Adults – Diagnosis, Management, and Future Directions: A Narrative Review

Article information

Abstract

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is defined as the presence of bacteria in the urine in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms. The prevalence of ASB increases with advancing age, particularly among older patients with underlying health conditions. ASB is especially common among residents of long-term care facilities; however, distinguishing ASB from symptomatic UTI in this population remains a significant clinical challenge. The frequent occurrence of ASB often results in unnecessary antibiotic administration, thereby contributing to the development of antibiotic resistance. Current clinical guidelines recommend screening for and treating ASB only in certain circumstances, such as prior to urological procedures or in pregnant women. There is a pressing need for improved diagnostic approaches to differentiate ASB more accurately from UTI, particularly in older adults. Reducing unnecessary urine testing and inappropriate antibiotic use may help prevent over-treatment and minimize associated risks, including Clostridium difficile infection and increased antimicrobial resistance.

HIGHLIGHTS

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is common among elderly individuals, particularly those in long-term care facilities. Despite its high prevalence, ASB typically does not harm health without needing treatment except in specific cases such as prior to urological procedures. Misdiagnosis of ASB as urinary tract infection (UTI) often leads to unnecessary antibiotic use known to contribute to resistance and cause adverse effects. Differentiating ASB from UTI is challenging due to overlapping nonspecific symptoms in elderly patients. Improved diagnostic tools, including biomarkers and molecular methods, are needed to guide treatment decisions, reduce antibiotic misuse, and enhance patient outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is defined as the presence of bacteria in the urine without urinary symptoms [1]. ASB is commonly observed and considered a form of commensal colonization, potentially playing a protective role against development of symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI) [2]. Unlike ASB, UTIs are diagnosed when urinary symptoms are accompanied by bacteriuria or when symptoms are nonspecific with the same bacteria cultured from both urine and blood samples. ASB has a high prevalence in elderly patients with positive urine cultures but nonspecific symptoms, makes diagnosing UTIs challenging [1,3,4].

ASB occurs in 3%–5% of young and healthy women. Its prevalence is 0.7%–27% in patients with diabetes and 4%–19% in the elderly [5,6]. Antibiotic treatment for ASB should be used sparingly because it can increase the rate of antibiotic resistance. Several clinical guidelines recommend screening and treating ASB only in specific cases, such as for prophylactic purposes before urological procedures or in pregnant women. For most ASB cases, treatment is not advised [1,2,7].

ASB is common in the elderly, primarily due to physiological changes associated with aging (e.g., altered bactericidal activity of prostatic secretions, decreased estrogen levels) and comorbidities [8]. To date, negative effects of ASB have not been demonstrated. ASB is known to have no impact on survival [8]. Treatment of ASB is not recommended in the elderly, with growing evidence suggesting that ASB might play a protective role against UTIs [6,9,10]. This is particularly challenging in residents of long-term care facilities (LTCFs) where ambiguous symptom reporting makes UTI diagnosis difficult, often leading to excessive antibiotic use. Such antibiotic use ultimately contributes to increased rates of antibiotic resistance. Here we summarize current evidence on ASB to reduce unnecessary diagnosis and treatment of ASB.

DIAGNOSIS

ASB is defined as the presence of at least 10⁵ colony forming unit (CFU)/mL of the same uropathogenic bacteria in 2 consecutive midstream urine samples from an asymptomatic individual [1]. For urine specimens obtained through intermittent catheterization, ASB is defined as the presence of bacteria at concentrations of at least 10² CFU/mL [11]. The diagnosis of UTIs in community-dwelling elderly individuals requires significant bacteriuria (≥10⁵ CFU/mL) accompanied by urinary symptoms, as in younger adults [1].

Diagnosing UTIs in the elderly can be challenging because their symptoms are often nonspecific. In a study of patients aged 65 years or older who visited the emergency department, 47% of patients with UTIs did not report urinary symptoms [12]. In another study, 18 out of 37 patients with bacteremic UTI aged 75 years or older did not have urinary symptoms [13]. In 26 elderly patients with bacteremic UTI, their main symptoms were confusion (30%), cough (27%), and dyspnea (28%), with new urinary symptoms appearing in 20% [13]. Nonspecific symptoms that may appear in acute UTI in the elderly include fever, syncope, weakness, delirium, foul-smelling urine, and changes in blood glucose levels [14-17]. However, these symptoms are also commonly observed in elderly individuals, making it unreliable to predict positive urine culture results based on these symptoms alone [18]. To distinguish UTIs from ASB, it is important to investigate nonurinary causes of fever and other nonspecific symptoms.

Diagnosing UTIs can be challenging even in elderly individuals with intact cognitive function. Distinguishing ASB from UTIs in elderly people with cognitive impairment is even more challenging [4]. Particularly among residents of LTCFs, multiple comorbidities can present symptoms similar to those of UTIs, further complicating diagnosis. In cases of cognitive impairment, there may be no complaints about any symptoms related to UTIs [19,20].

To address these diagnostic challenges, McGeer et al. have suggested diagnostic criteria for UTI according to recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Consensus Group with criteria being different depending on whether the individual has an indwelling catheter or not (Table 1) [21].

PREVALENCE

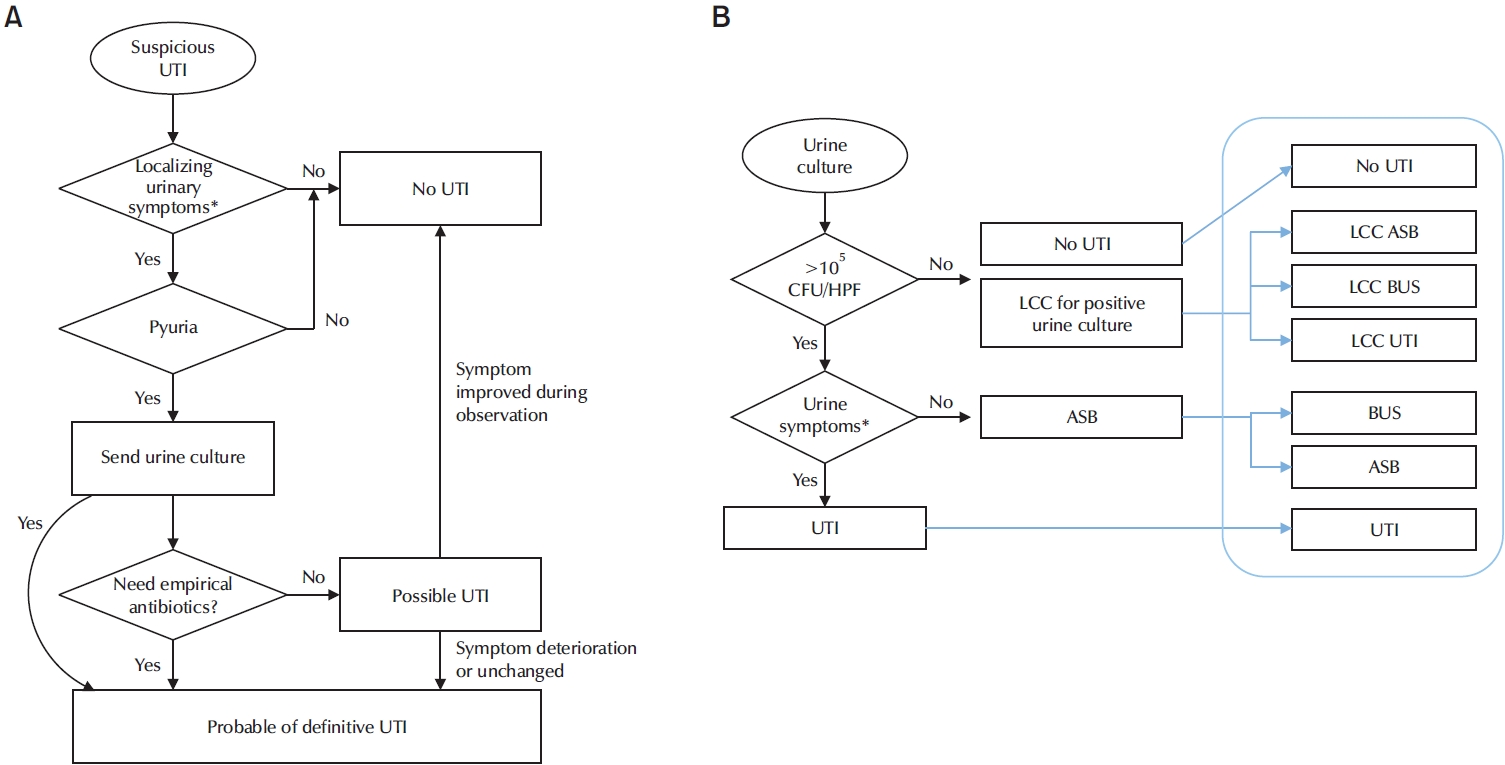

The prevalence of ASB increases with age. Among young women, the prevalence of ASB is 1%–2%, rising to 6%–16% in women aged 65–90 years and 22%–43% in women over 90 years old [3]. ASB is very rare in young men. However, its prevalence increases to 5%–21% in men aged 65 years and older, with the highest prevalence observed in those over 90 years old [3,6,22]. Among elderly residents of LTCFs, 25%–50% of women and 15%–35% of men have ASB, with a higher prevalence in individuals having severe disabilities [15,22]. Nearly 100% of elderly individuals with long-term indwelling catheters have ASB [4]. However, in patients with only nonspecific symptoms without distinct urinary symptoms, the prevalence of ASB may vary depending on how UTIs are defined (Fig. 1).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The etiology of ASB in the elderly is multifactorial. Risk factors for ASB include anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract (e.g., benign prostatic hyperplasia), hormonal and metabolic changes (e.g., decreased estrogen, diabetes), neurological disorders, and poor perianal hygiene, similar to those for UTIs [23]. ASB is particularly common among residents of LTCFs, the causes of ASB are comparable to that of UTIs. Differences in the occurrence of ASB by gender are largely due to anatomical and physiological changes, as is the case with UTIs Several factors contribute to the high frequency of UTIs among elderly residents in LTCFs; however, the relative significance of these factors varies between individuals. Similar to UTIs, age-related physiological changes, comorbidities that reduce immune response, such as diabetes, and interventions for managing voiding are the most important contributing factors. Notably, in institutionalized elderly individuals, neurogenic bladder-related complications are likely to have the greatest impact [15]. Many degenerative neurological diseases are commonly associated with neurogenic bladder, which can increase the risk of infection through mechanisms such as voiding dysfunction, elevated post-micturition residual urine volume, and vesico-ureteral reflux. Additionally, prior catheterization or the use of urinary devices further influences the likelihood of developing bacteriuria [15]. However, Escherichia coli is less frequently the causative pathogen compared to other causes of UTIs [23]. Elderly patients often have smaller bladder capacities, leading to frequent urination. Additionally, low fluid intake can result in concentrated, foul-smelling urine, making it difficult to distinguish between ASB and symptomatic UTIs [24].

The occurrence of bacteriuria varies depending on both host and microorganism characteristics. In most healthy adults, acute bacteriuria does not progress to persistent bacteriuria. Hooton et al. [25] have prospectively evaluated the occurrence of ASB in 796 sexually active women aged 18–40 years. They found that fewer than 1% of those with ASB developed persistent bacteriuria [25]. Additionally, persistent bacteriuria caused by the same strain is rare. Long-term bacteriuria caused by E. coli often has an attenuated virulence phenotype [26]. This supports the hypothesis that loss or disruption of virulence gene expression can facilitate long-term colonization and adaptation to the host environment.

Host characteristics can also affect the occurrence of bacteriuria. Differences in innate immune responses based on genetic background are also important. Decreased TLR4 expression and diminished innate immune responses are being associated with ASB [27]. Treatment of ASB can eliminate bacteriuria and reduce the occurrence of UTIs. However, there is a high likelihood of recolonization by the same or similar bacteria [28].

EVALUATION

To diagnose ASB, UTI must be excluded. Urinalysis is usually performed prior to deciding on empirical antibiotic treatment for UTIs. The prevalence of pyuria without bacteriuria is high in elderly individuals. Thus, the presence of pyuria alone is not helpful for diagnosing UTIs. While dipstick tests are generally accurate and sensitive, one study has shown that 96.9% of elderly patients with bacteremic UTIs are positive by dipstick test and approximately 90% of patients with isolated bacteriuria also have a positive dipstick result [29,30]. However, a meta-analysis estimated that the sensitivity for detecting UTIs in the elderly was only 82% [31]. Although nitrite test is more specific than leukocyte esterase, it has a lower sensitivity. Therefore, it cannot be used alone to exclude UTIs [29]. Microscopic urinalysis is also inaccurate, as 21.9% of patients with bacteremic UTIs have fewer than 10 leukocytes per high-power field in their urine samples [29].

Recently, Advani et al. [32] have proposed new criteria for ASB. In addition to the 3 phenotypes conventionally classified (no UTI, ASB, and UTIs), 2 new categories, lower urinary tract symptoms/other urologic symptoms and bacteriuria of unclear significance (BUS) are added. They have suggested that the existing 3 phenotypes do not sufficiently reflect clinical manifestations of patients. BUS is defined as cases 1 clinical criterion with or without other cause or cannot express symptoms (might have urologic criteria without clinical criteria). The conventional definition of ASB per the established criteria continues to mean that ASB has no specific signs or symptoms of a UTI or any clinical criteria (Fig. 2) [32]. Through a retrospective analysis, Advani et al. [32] have confirmed that there are differences in patient characteristics according to this new classification system, demonstrating the effectiveness of the new classification system. However, the extent to which treatment is needed has not been investigated yet.

Diagnostic approach of ASB. (A) Ideal diagnostic approach algorithm. (B) Diagnostic approach starting from urine culture and concept of continuum of UTI. ASB, asymptomatic bacteriuria; UTI, urinary tract infection; CFU/HPE, colony forming unit/high power field; LCC, low colony count positive urine culture with <100,000 CFU/mL; BUS, bacteriuria of unclear significance.

MANAGEMENT

Antibiotics are commonly used in the elderly with fever and other nonspecific symptoms. Since UTIs are among common causes of fever, urine cultures and antibiotic treatment are often administered regardless of urinary symptoms. Inappropriate treatment of ASB confirmed by urine cultures occurs frequently not only in the United States but also in Canada and Europe. According to a recent meta-analysis study, the rate of inappropriate treatment for ASB was 45% in the United States, 58% in Canada, and 47% in Europe [33]. The American Geriatrics Society has listed unnecessary antibiotic use for ASB as one of the 5 most overused medical services [33].

There have been reports indicating that the length of hospitalization for ASB patients is longer due to inappropriate treatment of ASB [34,35]. Antibiotic treatment for ASB can increase the risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including Clostridium difficile infections, as well as the risk of antimicrobial resistance [36]. A recent study has reported that E. coli detected in ASB patients shows greater antibiotic resistance than E. coli isolated from UTI patients, although the number of patients is small [37]. Ultimately, the uncertainty in distinguishing between ASB and UTI may partially explain the "overtreatment" of ASB patients.

In the elderly, routine screening and treatment for ASB are not recommended. Screening or treatment for ASB is not recommended either women with diabetes, elderly individuals residing in the community or institutionalized settings, patients with spinal cord injury, or those with indwelling catheters [1]. However, screening and treatment for ASB in the elderly are recommended in 2 specific situations based on randomized trial results: prior to transurethral resection of the prostate and before urological procedures where mucosal injury is anticipated (Table 2) [1].

Strategies to reduce treatment of ASB include minimizing unnecessary urine culture to reduce overdiagnosis, mitigating ASB occurrence through immunomodulation, and reducing inappropriate antimicrobial use through appropriate antimicrobial stewardship programs [9].

UTIs are common causes of fever, leading to routine urine culture tests in elderly patients with fever, regardless the presence of urinary symptoms. It is clear that elderly patients presenting with urinary symptoms or signs attributable to urological causes should undergo urine testing. However, to reduce the proportion of unnecessary urine tests in acutely ill elderly patients, prescribing practices by physicians need changes. One recommended strategy is to refrain from automatically reporting urine culture results and perform urine cultures only when it is absolutely necessary and upon request [38]. Another approach involves automatically canceling urine cultures when urinalysis results are negative. For instance, if dipstick testing, microscopic urinalysis, or urinalysis shows negative results, then urine culture should be canceled. It have been shown that canceling urine culture orders for elderly patients with negative dipstick tests reduce inappropriate antibiotic treatments without compromising patient safety [29,30].

The use of probiotics or immunomodulating agents has also been proposed as a method to reduce the incidence of UTIs. Krebs et al. [39] have administered a lyophilized lysate of 18 E. coli strains to patients with spinal cord injuries for over 12 months and found that it can significantly decrease the incidence of recurrent UTIs and notably increase the proportion of patients who have remained UTI-free. A meta-analysis reported in 2013 evaluated the therapeutic effects of Lactobacillus for recurrent UTIs [40]. Recurrent UTIs were significantly reduced in patients who received Lactobacillus, with an odds ratio of 0.51. Lactobacillus helps to create an acidic environment by producing lactic acid and other acids. Vaginal Lactobacillus protects the female urogenital tract from colonization by pathogens, so it can contribute to the prevention of urogenital infections [41]. Although, while these interventions appear effective in reducing UTI incidence, further studies are needed to determine their roles in decreasing the occurrence of ASB.

To reduce treatment of ASB, it has been recommended to monitor stable patients without urinary symptoms, signs, or fever for 48 hours without antibiotics [4,42]. A key challenge is to determine which elderly patients with nonspecific symptoms or signs can be observed without treatment instead of receiving empirical antibiotic treatment at presentation. Most experts recommend initiating antibiotic therapy for elderly patients with fever (generally defined as body temperature ≥38°C). In contrast, stable, afebrile patients without localized urinary symptoms or signs may be considered for observation. There are 3 management strategies to reduce unnecessary urinalysis as shown below [43].

(1) Determine whether the patient’s symptoms have an extraurinary source.

(2) Patients with clear extraurinary symptoms should not undergo urinalysis or urine culture.

(3) For patients without extraurinary causes of symptoms: (a) Urinalysis may be performed as needed, but additional reflex microscopic examination should be avoided. (b) If the dipstick test is negative, urine cultures should be canceled. (c) Classify patients as stable or unstable: (i) Stable patients without fever: Closely monitor for 48 hours without antibiotics. Perform urinalysis only if needed and perform urine culture only if the dipstick test is positive. Treat with empirical antibiotics if symptoms worsen or persist, and investigate other potential causes or diagnoses. (ii) Unstable patients: treat with appropriate antibiotics.

However, some studies have compared the effectiveness of expert-led education programs aimed at improving inappropriate antimicrobial treatment of ASB and indicated that such interventions fail to bring about sustained changes in ASB management [44]. This highlights the need for a more systematic solution to address the issue [44].

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In the elderly, ASB is often treated inappropriately with antibiotics even though it does not require treatment. This is because the diagnosis of UTIs in the elderly is often ambiguous. Therefore, there is a need for improved diagnostic tests to differentiate ASB from UTIs in the elderly [45]. Some studies have utilized the analysis of inflammatory cytokine levels in urine to distinguish ASB from upper UTIs. Kjölvmark et al. [46] have compared urinary heparin-binding protein and urinary interleukin-6 (IL-6) in LTCF residents, finding that both levels are significantly lower in ASB patients than in those with UTIs. Additionally, Sundén and Wullt [47] have compared urinary IL-6 and IL-8 levels in patients with ASB and UT and found that both urinary IL-6 and IL-8 levels are low in ASB patients with only IL-6 showing a significant increase during UTI episodes. The use of novel biomarkers may aid in distinguishing ASB. The risk of severe infection and the need for treatment in ASB can be predicted based on bacterial virulence factors. For example, several virulence factors of E. coli are associated with pyelonephritis [48]. Therefore, rapid molecular diagnostic tests to detect the presence and pathogenic potential of E. coli could be helpful in determining whether to administer antibiotics.

CONCLUSIONS

Although ASB is commonly observed in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, ASB is not known to have a negative impact on health. The distinction between ASB and UTIs is often ambiguous, leading to frequent inappropriate antibiotic use, which can result in serious issues such as antibiotic resistance. Treating ASB is not recommended except in specific cases, such as prior to urological procedures or during pregnancy.

To clearly distinguish ASB from UTIs in elderly patients, clinicians must adopt a symptom-based approach and carefully evaluate urine test results. Development of new classification systems, inflammatory biomarkers, and molecular diagnostic tools can aid in distinguishing ASB from UTIs, reduce unnecessary antibiotic use and improve patient safety.

Notes

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization, KHK and HJY; Methodology, HJY.; Software, HJY; Validation, HJY.; Formal Analysis, KHK; Investigation, KHK and HJY; Resources, KHK.; Data Curation, HJY; Writing - Original Draft Preparation, KHK and HJY; Writing - Review & Editing, KHK and HJY; Visualization, KHK; Supervision, HJY; Project Administration, KHK and HYJ; Funding Acquisition, none.