Korean Translation of the GRADE Series Published in the BMJ, ‘Use of GRADE Grid to Reach Decisions on Clinical Practice Guidelines When Consensus Is Elusive’ (A Secondary Publication)

Article information

Abstract

This article is the last of a series providing guidance for the use of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system for rating the quality of evidence and grading the strength of recommendations in systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines. Formulating recommendations with the applicable evidence can be difficult due to the large and diverse nature of guideline committees. This article describes a simple technique called the GRADE grid for clarifying the opinions from guideline panels, dealing with disagreement, and achieving consensus among guideline panels. The grid may be helpful for any guideline groups who want to use GRADE to develop their guidelines and achieve consensus or understand the patterns of uncertainty that surround the interpretation of scientific evidence.

임상진료지침에서 합의에 도달하기 어려운 경우 GRADE의 이용

1.임상진료지침 개발위원회의 매우 다양한 구성은 합의(Consensus)에 이르기 어렵게 만듭니다. 본 논문은 권고를 분명히 하기 위한 단순한 방법을 설명하고자 합니다.

임상진료지침은 임상진료현장(clinical practice)에 영향을 미치는 중요한 수단이 되었습니다. 많은 지역, 국가 및 국제 사회는 이제 관련 임상 영역을 확인하고, 핵심 질문(clinical questions)을 만들고, 적용 가능한 근거(evidence)를 검토하고, 임상의사와 환자가 따라야 한다고 믿는 권고(recommendation)를 도출하는 과정을 수행합니다.

수년에 걸쳐, 최적의 권고 사항을 도출하는 데 필요한 다양한 전문가(임상 전문가[content experts], 방법론자, 일선 임상의사, 환자 대표[patients’ representative])를 고려하여, 진료지침 개발 패널의 규모는 커져 왔습니다. 결과적으로 다양한 패널은, 모든 참가자가 의견을 갖고 토론 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있도록 보장하고, 투명성을 보장하고, 불일치를 처리하고, 합의를 달성하고, 합의가 불가능한 상황을 해결하는 등, 의사결정 과정에서 어려움을 겪습니다.

진료지침 개발 패널은 종종 이러한 문제를 처리하기 위해 비공식 절차를 이용합니다. 그러나 비공식적 절차는 소규모 또는 중간 규모의 그룹 상호 소통의 특수성에는 취약합니다. 시간적 압박, 피로, 임상 영역에 대한 전문성 부족, 가장 중요한 것은 저명한 전문가의 결정과 같은 요인이 임상진료지침 개발 과정에 매우 큰 영향을 준다는 것입니다.

진료지침 개발 과정에 관심있는 사람들은 이러한 문제를 해결하기 위한 두 가지 전략을 개발했습니다. 첫번째는 구조화된 접근 방식을 사용하여 관련 근거를 수집, 분석 및 요약하고 해당 증거를 사용하여 임상 권고를 도출하고 권고 등급을 결정합니다. 이러한 접근 방식은 Grading of Recom-mendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) 그룹에 의해 개발되었으며 진료지침 개발을 위해 점점 더 널리 사용되고 있습니다[1-6]. 두번째는 모든 진료지침 개발 패널이 동등하게 합의 과정에 기여할 수 있는 공식화된 절차입니다[7,8].

이 논문에서는, 합의 도출 과정을 간략하게 검토하고, 질 관리(quality improvement) 및 진료지침 개발 그룹(패혈증 환자 살리기 캠페인[Survival Sepsis Campaign])을 소개하고, 패혈증 환자 살리기 캠페인 그룹에 의해 개발되고 수행된 도구, GRADE grid 방법론을 소개하고자 합니다[9].

2. 공식적인 합의 도출 방법

합의를 도출하기 위해 가장 널리 사용되는 방법은 델파이법(Delphi method), 명목집단기법(nominal group tech-nique) 및 이 두 가지 접근 방식의 조합입니다. 원래 전쟁에 사용되는 기술(technology on warfare)의 효과를 예측하는 데 사용되었던 Delphi 방법은 여러 이해 당사자(shake-holders) 또는 전문가의 의견을 체계적으로 수집합니다. 델파이법에는 많은 수의 참가자가 포함될 수 있으며, 이 과정에서 참가자는 두 번 이상의 설문조사에 답하며 일반적으로 직접 만나지 않고 독립적으로 작업합니다. 각 회차(round)가 끝나면 진행자(facilitator)가 이전 회차의 참가자의 의견(judgement)과 그 이유를 익명으로 요약하여 제공합니다. 참가자는 다른 구성원의 답변에 비추어 이전 답변을 수정할 수 있습니다. 일반적으로 이 과정에서 답변의 범위는 줄어들고 그룹은 합의를 도출할 수 있습니다. 모든 절차는 사전 정의된 중지 기준(예: 총 회차수, 합의 도출, 결과의 안정성[stability of results])에 이르면 종료됩니다[9,10].

명목집단기법은 대면회의를 통하여 소수의 전문가로부터 의견을 이끌어냅니다. 모든 사람에게 동등하게 의견을 개진하며, 주최자(organizer)에 의해 참가자들에게 주어지는 공식적인 피드백, 구조화된 상호 토론기법(structured face to face interactions), 참여자의 의견(idea) 산출 또는 의견의 우선순위 선정과 같은 참여자 각자의 의견 산출 및 평가 과정(period of private activity [non-interacting]), 그리고 문제해결을 위한 명확한 방법이 제시됩니다. 합의 도출을 위해 모든 참가자가 여러 권고들을 최고에서 최저로 순위를 정하게 됩니다.

이 두 가지 방법은 진료지침 개발 과정뿐만 아니라 합의가 도출되어야 하는 다양한 상황에서 사용됩니다. 예를 들어, 이 방법들을 통해 국가 연구 우선순위를 선정하고 국제 교육프로그램을 개발하는 데 유용한 것으로 알려져 있습니다[11,12]. 이러한 방법의 변형은 일반적으로, 예를 들어, 명목집단기법에서 권고에 순위를 매기기보다는 투표를 하는 것이 일반적이며, 각 방법은 매우 다양하게 이용될 수 있습니다. 특별히 진료지침 개발을 위해 제안된 다른 방법들도 있습니다[9,13].

3. 패혈증 환자 살리기 캠페인

10개국 이상, 50명이 넘는 전문가들이 패혈증 환자 살리기 캠페인의 일환으로 중증 패혈증 및 패혈성 쇼크 관리 진료지침 개발에 참여하였습니다[14]. 캠페인 가이드라인의 초판은 2004년에, 가장 최신판은 2008년에 출판되었습니다. 2008년 가이드라인은 근거수준(quality of evidence)과 권고등급(strength of recommendations)을 평가하는 GRADE 방법론을 사용하여 개발되었습니다[1]. GRADE는 근거수준을 ‘높음’, ’중등도’, ‘낮음’ 및 ‘매우 낮음’으로 분류합니다. GRADE를 이용하여 관찰 연구(observational data)의 근거수준은 ‘낮음’에서 시작하여 ’중등도’ 또는 ‘높음’ 범주로 높일 수 있으며, 무작위 대조군 연구(randomised trials)에서 나오는 근거수준은 ‘높음’에서 연구의 설계 및 수행결과에 따라 낮출 수 있습니다. 근거수준 결정 과정은 고도로 구조화되어 있지만 주관적인 판단이 필요하므로 의견 차이가 발생합니다.

주관적인 판단은 권고등급(‘강함[strong]’과 ‘약함[weak]’)을 결정함에 있어서도 필요합니다. 진료지침 개발 패널은 권고의 바람직한 효과가 바람직하지 않은 효과보다 클지, 권고 강도는 권고에 대한 우리의 신뢰도를 반영하는지 결정하여야 합니다. 중재(intervention)에 대한 강한 권고(strong recommendation)는 중재의 바람직한 효과(유익한 건강 결과[beneficial health outcome], 의료진 및 환자에 대한 부담 감소, 비용 절감)가 바람직하지 않은 효과(위해[harm], 부담 증가 및 비용 증가)보다 분명히 클 때 이루어집니다. 약한 권고(weak recommendation)는 바람직한 효과가 바람직하지 않은 효과보다 크지만 진료지침 개발 패널이 효과의 차이가 적어 확신(confidence)이 부족한 경우 근거수준이 낮거나(중재의 편익[benefit]과 위해[risk]가 불확실한 경우) 효과의 차이가 거의 없을 때 이루어집니다.

패혈증 환자 살리기 캠페인의 경우 새로운 연구결과가 지속적으로 보고되는 급변하는 의료환경에서 의견의 불일치를 해결하고 근거를 해석하며 권고를 도출하기 위한 보다 공식적인 합의 과정의 필요성을 인식했습니다. 이러한 요구는 캠페인 진료지침 이전 판에 대한 비판에서 시작되었으며 강조되었습니다[15]. 이 비판은 이해 상충과 제약업계와 같은 이익단체의 후원을 받은 저자의 연구조작에 초점을 맞추었습니다.

4. 캠페인 합의 도달과정

합의관련 본 회의(plenary consensus conference, 캠페인의 모든 참가자 및 조직의 회의)에서 캠페인 위원과 집행위원회가 사용한 합의 도달 기법; 각 특정 주제 또는 중재에 대한 소규모 전문가 그룹; 전문가 그룹의 결과를 평가하는 15-30명으로 구성된 두 차례의 수정 명목집단회의(modified nominal group meeting); 그룹의 반복 토론에서 사용된 수정 델파이법(이메일 이용)을 사용하였습니다. 이러한 과정에서 나타난 불일치의 주요 영역은 특정 권고의 강도였습니다. 합의도출의 어려움으로 인해 보다 공식적인 접근 방식의 필요성이 강조되었습니다. 따라서 캠페인은 다음 규칙에 따라 수정 명목집단회의(투표를 이용한)를 진행하였습니다. 첫째, 지속적인 불일치 영역에서 특정 중재에 대한 권고(특정 대안 중재 [alternative]와 비교하여)는 참가자의 최소 50%가 권고에 해당하는 중재를 선호하고, 20% 미만이 대안 중재를 선호하는 경우에 이루어졌습니다. 이 기준을 충족하지 못하면 권고를 내리지 않았습니다(no recommendation). 둘째, 권고 강도가 ‘약함’이 아닌 ‘강함’으로 평가되려면 참가자의 70% 이상이 강한 권고에 동의가 필요하였습니다.

5. GRADE Grid의 적용

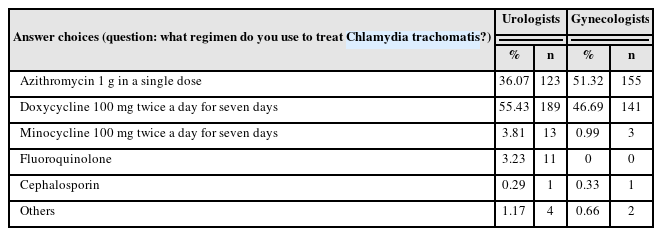

GRADE 방법론에서 진료지침 개발 패널의 다양함을 확인하기 위해 GRADE grid를 설계하고 실행하였습니다(Table 1 and Appendix 1) [16]. Grid를 통해 합의 패널은 근거에 기반한 특정 중재의 편익과 위해의 차이에 대한 각각의 관점을 기록할 수 있습니다. 이러한 평가를 통해 각 중재의 사용 여부에 대한 권고 강도를 결정합니다. 각 제안된 권고는 중립적인 방식으로 표현됩니다(“…의 사용”).

GRADE grid for recording panelists’ views in the development of guidelines (including examples of propositions from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and number of panelists who voted for each option)

Grid를 사용하기 위해, 모든 참가자는 권고 강도와 권고 강도 결정에 영향을 미치는 요인을 설명하는 지침을 받았습니다(Tables 2, 3 and Appendices 2, 3) [16]. 각각의 투표는 권고로서 제안된 임상질문과 패널들의 다양한 동의 여부를 다루었습니다. 패널들은 제안된 권고(인구집단[popula-tion], 중재[intervention], 비교중재[comparator] 및 건강 결과[outcome]에 대한 명시적 설명), 근거 제시, 의견 불일치에 대한 잠재적 원인(Table 2 and Appendix 2) [16] 고찰을 검토한 후 양식을 완성했습니다.

6. 과정 예시

이미 GRADE에 대해 잘 알고 있는 참가자들은 쉽게 사용할 수 있는 양식을 개발하였습니다. 과정 소개, 교육, 관련 질문에 답변에 10분이 걸리지 않았습니다. 제안에 대한 동의 여부 및 관련 근거 제시 후 각 권고에 대한 양식을 작성하는 데 2분이 걸리지 않았습니다. 지원 담당자는 투표를 표로 작성하고 결과를 발표하였습니다. 다음 예제는 GRADE grid가 어떻게 도움이 되었는지를 강조해서 보여줍니다.

1) 권고 명확히 하기

패혈성 쇼크에서 스테로이드 사용과 관련하여 참가자의 의견을 명확히 하기 위해 두 가지 제안된 권고를 검토했습니다. 첫번째 권고는 수액 및 혈관수축제(혈압을 높이는 약물)를 사용한 초기 치료에 반응하지 않는 패혈성 쇼크가 있는 성인에서 스테로이드 사용(사용하지 않는 경우와 비교)을 다루었습니다. 두번째 권고는 초기 치료에 반응하는 패혈성 쇼크가 있는 성인에서 스테로이드 사용을 다루었습니다. 스테로이드 소위원회의 초기 제안은 첫번째 그룹(수액 및 혈압상승제에 반응하지 않는 경우)에서 스테로이드 사용을 강하게 권고하고 두번째 그룹(수액 및 혈관상승제에 반응하는 혈압)에서는 스테로이드를 사용하지 않도록 강하게 권고하는 것이었습니다. 전체 위원회에서는 치료에 대한 반응을 정확하게 정의할 수 없지만 서로 상반되는 두 가지 강한 권고에 의문을 제기하였습니다. 따라서 우리는 grid를 사용하여 이 두 가지 권고를 평가했으며, 이는 강한 권고보다는 약한 권고에 대한 명확한 선호도를 제공했습니다(Table 1) [16].

2) 불확실성 보여주기

광범위한 연구에도 불구하고 선택적 소화관 제균(selective digestive decontamination) (기계호흡 환자의 감염을 예방하기 위한 예방적 항생제 사용)은 여전히 논란의 여지가 있습니다. 이 경우 공식적인 투표 절차 없이는 합의를 얻을 수 없다는 것이 분명했습니다. Table 1은 이 치료의 잠재적 효과에 대한 불확실성의 정도를 보여주며, 선택적 소화관 제균의 사용 여부(약한 권고)에 대해 동의 또는 반대가 동일하게 나타났으며, 상당한 부분이 결정되지 못하였습니다[16]. 패널 50% 이상이 권고의 방향성(사용 권고 또는 사용을 권고하지 않음)에 동의하지 않았기 때문에 위원회는 사용 여부에 대한 권고를 내리지 않기로 결정했습니다. 투표의 결과로 추가적인 논의를 하지 않게 되었으며, 그렇지 않았다면 오랫동안 논의가 계속되었을 것입니다.

결론

이 합의 과정에서 가장 어려운 부분은 인구집단, 중재 및 비교중재를 포함한 임상 질문(제안된 권고)의 정확한 정의와 모든 가능성을 허용하는 중립적 방식으로 권고를 표현해야 한다는 점이었습니다. 합의를 도출하기 어려운 경우, 진료지침 개발 패널이 정확한 임상 질문을 결정하였을 때, 중재의 바람직한 결과와 바람직하지 않은 결과 사이의 균형에 대한 패널들의 의견을 탐색하기 위해 구조화된 접근 방식을 사용할 것을 제안합니다. 여기에 설명된 GRADE grid는 가능한 모든 대안의 가능성을 평가하기 위하여 추가적인 논의를 할 수 있고 의견을 조사할 수 있는 효과적인 방법을 제공합니다.

패혈증 환자 살리기 캠페인에서 GRADE grid는 과학과 근거 및 근거의 해석에 대한 다양한 견해를 가진 전문가들에 의해 명백히 결론에 이르지 못한 주제에 대한 합의 및 종결이 신속히 이루어지도록 하였습니다.

투표 규칙은 캠페인 작업에 따라 다릅니다. 우리는 투표의 익명성을 유지하기로 결정했습니다. 이는 의견을 자유롭게 표현할 수 있는 최상의 기회를 제공하기 때문입니다. 공개 투표는 이해 상충으로 인한 투표를 제한할 수 있기 때문입니다. 그러나 우리는 명목집단회의와 함께 GRADE grid를 사용하는 비공개 투표가 그러한 갈등(존재하는 경우)이 균형을 이루거나 그 영향을 최소화하도록 보장할 것이라고 믿습니다.

GRADE 근거요약표를 준비하려면 광범위한 준비(resource)가 필요하지만 grid를 사용은 그렇지 않습니다. 우리는 GRADE grid가 패널들의 견해와 동의 및 비동의 정도를 신속하고 명확하게 할 수 있을 것이라고 생각합니다. 우리는 grid가 GRADE를 사용하는 모든 진료지침 개발 그룹에 있어 합의를 도출하거나 근거 해석을 둘러싼 불확실성을 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 믿고 있습니다.

Supplemental Materials

Notes

This article is the secondary publication (complete translation in Korean) of the article originally published in the BMJ in English (Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. 2008;337: a744). The Editor in-Chief of Urogenital Tract Infection decided to publish this secondary publication for the reader's sake, and it was approved by BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group takes no responsibility for the accuracy of the translation from the published English language original and are not liable for any errors that may occur.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article are reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.J.J.: translating the article, and drafting the manuscript, E.C.H., D.K.K., H.W.K., J.Y.K., and H.W.K.: helping to translate and draft the manuscript, J.H.J.: contacting BMJ editorial office to get the approval, helping to translate and draft the manuscript, and final approval.